Lead Time Crunch #4

Hi, this is a mini newsletter for engineers thinking about management.

I’m Péter Szász, writing about my decades of engineering leadership experience on my blog, and mentoring aspiring and first-time Engineering Managers on this path. See more about what I can offer to you at leadtime.tech.

In this newsletter, I pose a weekly EM challenge and leave it as a puzzle for you to think about before the next issue, where I share my approach, one possible solution amongst many.

Last week, I wrote about a surprising discussion between Ethan, a long-time developer at the company, and David, his manager. Ethan, just coming back from a long vacation, announced he wants to quit. Read the details here first if you missed it, otherwise the following will not make much sense.

Last Week’s Challenge

In this case, if I would be David, Ethan’s manager, my focus would be balancing between giving support to a distressed team member and convincing him to stay at the company. The key to achieving both is to maintain his trust in our relationship. There’s some foundation for that because he felt safe sharing his feelings. But the level of trust is not very high, if the severity of these issues came as a surprise to me.

These two goals, supporting Ethan and ensuring he stays at the company, are not equal.

Supporting members of a team in their careers is one of the three explicit roles of an Engineering Manager. (The other two are delivery aligned with company goals and building and maintaining a healthy team.) While I would love to continue working with Ethan, I don’t want that if it’s not the right job for him. Therefore, supporting him is more important than making sure he stays on board at all costs. If he’s happy and not quitting (now), that’s one of the possible outcomes of that support.

So, my goal is to increase his trust that I want the best for him. I need to frame the discussion as a discovery of his preferences, a collaboration in finding out what’s best for him personally and professionally, and once that’s done, assessing how this aligns with the needs and means of the company.

There are risks with this approach: I might lose credibility if I don’t address his concerns (”Why are you still working here if you agree that this place sucks?!”); I might go overboard and promise something I cannot deliver (regarding, for example, his promotion aspirations); I might be tempted to make exceptions for him that I can’t offer for others on the team; or I may forget my role as his manager and start to act like a friend, risking the efficiency of our future work together. I should be mindful of avoiding these traps.

After thinking these priorities through, I would take an empathetic listener approach during this first talk. If I validate his judgment on the situation, that could increase the trust, but on the other hand, confirming all the bad things he’s experiencing at the company would diminish the chances of me convincing him to stay, let alone losing my credibility as a colleague. So instead of validating his assessment, what I can validate is the effect of this perception on him, the feelings he’s going through. Instead of “You’re right, it’s crazy that we switched product direction three times this year,” I would say something like “I can see how these frequent changes are affecting you and that you’re upset about them”.

After he experienced some relief from being able to say these things out loud to me, I would carefully focus on the future. I want to get two messages out loud and clear for him: First, the company is grateful for his contributions and would like to continue working with him. I cannot make any promises, but I will do what I can to be flexible in accommodating his needs. Second, regardless of the outcome of these discussions, I will support him in finding the best next step, even if it would mean outside of this team or company. But before he makes his decision final, I’d love to have a chance to figure out, together with him, how a job would look like that he would be motivated to take.

If he agrees, I’d propose him to take some time and think about what it is he wants to achieve. He mentioned career aspirations, I’m happy to support him with a structured approach to grow the skills and offer him the experiences that any title or position he’s motivated to work towards needs. I want to understand his dream job so we can figure out how we can increase the overlap between that and what this company can offer him.

Finally, to keep our options open and avoid distracting the team, I’d ask him to keep this discussion between us only until we had a chance to better understand what he needs and what the company can offer. The exception I would ask his permission for is to let me share what we talked about with my manager, so I can discuss what flexibilities we have in shaping our job offer to Ethan.

If everything goes well, he will feel a release of tension after this discussion. There’s a risk that by alleviating his pain, he feels less motivated to change, pushing him towards frustration and burnout again in a few months. It’s my job to keep him accountable for his plans, even if it’s a difficult conversation when I’m happy he no longer wants to quit. So, I’d put it immediately on the agenda of our next 1:1 to discuss his “dream job”, and keep on continuing working these issues out. As I said above, it’s also important not to make exceptions for him: I shouldn’t offer anything for Ethan that I wouldn’t give to anyone else equally well performing in their role.

Did you ever have a top performer wanting to quit your team? How did you handle that situation? Did I miss something from my approach above? Let me know in the comments!

This Week’s Challenge

But now, let’s move on to a new exercise for the week!

It’s been 10 months you’ve been working at your current company, a tech startup delivering a B2C SaaS application. You’re the Engineering Manager of a cross-functional team, owning an important area of the product. While the team and the tech stack have their pain points, things are going okay: you had a successful onboarding, have a solid plan to improve struggling areas, and generally get good feedback from your manager, stakeholders, and peers.

The VP of Engineering, the boss of your manager, has a habit of taking 30-minute skip-level one-on-one meetings with everyone in her 120-strong organization. Because of the size of it, she can only do this with one person once a year. While you regularly meet her in group meetings and during random occasions in the office, the last time you had a one-on-one with her was during your onboarding, and never did these kinds of skip-level talks.

How do you prepare for this meeting?

Think about what your goal would be and what risks you’d like to avoid in this situation. I’ll share my approach next week. If you don’t want to miss it, sign up here to receive that and similar weekly challenges in the future:

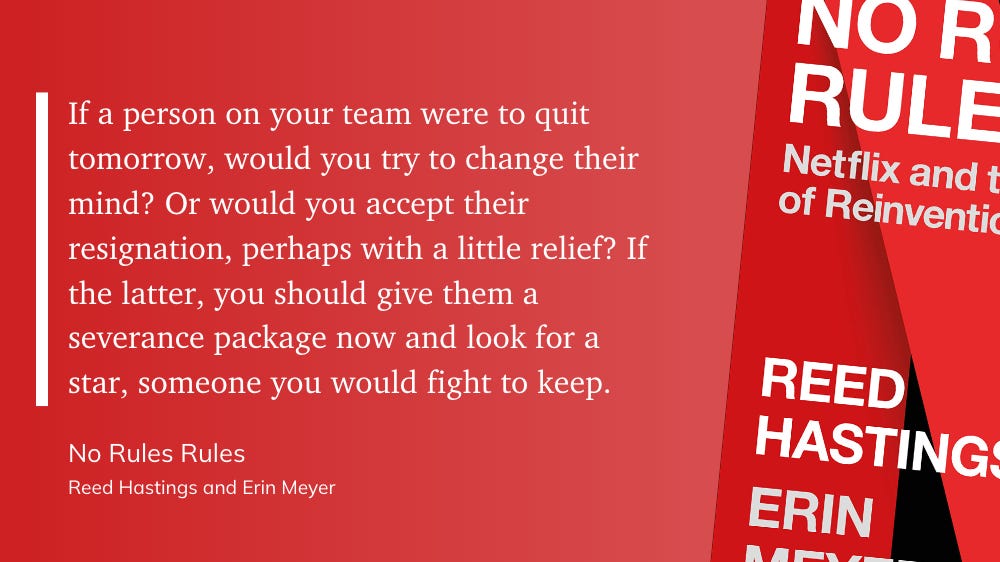

Until then, a small piece of inspiration slightly tied to last week’s challenge:

See you next week,

Péter